If you are a parent, you have no doubt experienced what I refer to as “packing for an expedition.” It’s that moment when you survey the pile of gear about to be loaded into the mini-van and wonder why it requires a gross ton of supplies to meet the weekend needs of a fourteen-pound baby.

Diapers, stroller, pack-n-play, blankets, a dozen bibs, formula, wipes, a small cache’ of brightly colored toys, five pacifiers, nine outfits, travel bath tub, etc.

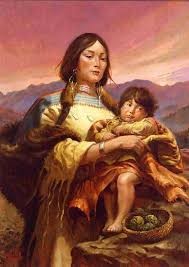

In 1805 Sacajawea faced a similar baby-on-board dilemma. Well, not really similar. Allow me to back up the story a few chapters.

Sacajawea’s history reads like a Greek tragedy. Captured by a war party of Hidatsa Indians when she was only 12, she was taken from her Shoshone tribe in modern day Idaho to North Dakota. There she was sold as a slave to a French-Canadian fur trader named Toussaint Charbonneau. She and another Shoshone girl were later “claimed” as his wives. Though this series of circumstances were horrible by any standards, the experience made her an effective interpreter.

In November 1804, Lewis and Clark arrived at her village, and put in for the winter. A few months later seventeen-year-old Sacajawea gave birth to her son, Jean-Baptiste. Lewis and Clark surmised that when the expedition met the Shoshones, Sacagawea would be able to converse with them and then translate to Hidatsa for Charbonneau. He would translate in French to the Corps’ Francois Labiche who would make the final translation in English to Lewis and Clark. (If you have ever played the campfire game “Telephone” you can appreciate what may have gotten lost in the multiple translations.)

Little Jean Baptiste was less than two months old when the Corps of Discovery departed to continue the trek to the Pacific Ocean. All Sacajawea brought was what she could carry on her back and what would fit in a canoe--No Coast Guard approved flotation devices included. Sacagawea was the only woman to accompany the 33 members of the permanent party to the Pacific Ocean and make the return trip. In addition to translation, her role with the Corps included collecting edible plants, roots and berries which were used as food and medicine.

In May several boats overturned and Lewis noted, “the Indian woman to whom I ascribe equal fortitude and resolution, with any person on board at the time of the accedent, caught and preserved most of the light articles which were washed overboard.”

Four days after that entry, the captains named "a handsome river of about fifty yards in width" the Sacagawea "or bird woman's River, after our interpreter the Snake woman." The Sacagawea River empties into the Musselshell a few miles south of where the latter joins the Missouri in northeastern Montana.

On August 12, 1805, Captain Lewis and three men scouted 75 miles ahead of the expedition’s main party, crossing the Continental Divide at today’s Lemhi Pass. The next day, they found a group of Shoshones. Not only did they prove to be Sacagawea’s band, but their leader, Chief Cameahwait, turned out to be none other than her brother. Through the labyrinth interpreting chain the expedition was able to purchase the horses it needed.

Sacagawea turned out to be incredibly valuable to the Corps when they encountered new tribes. As Clark noted on October 19, 1805, “the Indians were inclined to believe that the whites were friendly when they saw Sacagawea. A war party never traveled with a woman -- especially a woman with a baby.”

On November 24, 1805, when the expedition reached the place where the Columbia River emptied into the Pacific Ocean, the captains held a vote among all the members to decide where to settle for the winter. Because of the respect she had earned, Sacagawea’s vote was counted equally with those of the captains and the men. While there at Fort Clatsop, local Indians told the expedition of a whale that had been stranded on a beach some miles to the south. Clark assembled a group of men to find the whale and possibly obtain the oil and blubber. Sacagawea had yet to see the ocean, and after willfully asking Clark, she was allowed to accompany the group to the sea.

As Captain Lewis wrote on January 6, 1806, “The Indian woman was very importunate to be permitted to go and was therefore indulged. He observed that she had traveled a long way with us to see the great waters, and that now the monstrous fish was also to be seen, she thought it very hard she could not be permitted to see either.”

The Corps returned to the Hidatsa-Mandan villages on August 14, 1806, marking the end of the trip for Sacagawea, Charbonneau, and their boy, Jean Baptiste. When the trip was over, Sacagawea received nothing, but Charbonneau was given $500.33 and 320 acres of land.

Charbonneau Toussaint was not suited to tilling the soil, and, moreover, both he and Sacagawea longed to return to their former lives on the upper Missouri. Selling his land to Clark for $100, he took employment with the Missouri Fur Company. He and Sacagawea departed leaving their son Baptiste in the care of Clark, who would see to the boy’s education.

Sacagawea had endured so much in her life and had been such an amazing asset to the expedition that a happy ending was certainly deserved. But that was not to be. Six years after the expedition, Sacagawea gave birth to a daughter, Lisette. Shortly after on December 22, 1812, the Shoshone woman died at age 25 due to what later medical researchers believed was a serious illness she had suffered most of her adult life.

Eight months after her death, Clark legally adopted Sacagawea’s two children, Jean Baptiste and Lisette. Baptiste was educated by Clark in St. Louis, and then at age 18, was sent to Europe. It is not recorded whether Lisette survived past infancy. Charbonneau remained among the Mandans and Hidatsa along the upper Missouri until his death in 1840.

Sacagawea’s legacy and contribution to the Core of Discovery has been never fully appreciated. Undertaking a 2800-mile journey into the wilds of the American west, with an infant, certainly gives Sacagawea top billing over the fictional Wonder Woman.

To learn more about Sacagawea or the expedition there are scores of books and articles. However, for those who would prefer to watch their history, check out PBS’ Lewis & Clark: The Journey of the Corps of Discovery.